The Ruffed Grouse Society & American Woodcock Society (RGS & AWS) recently signed the Sugar Creek Stewardship Agreement on the Nantahala National Forest in North Carolina. The project, previously shelved […]

Southern Appalachian

Take Action: Support White Pine Removal Project on the George Washington and Jefferson National Forests

RGS & AWS Members, The White Pine Removal Project will help meet the habitat needs for ruffed grouse and a broad suite of forest wildlife by increasing forest age class […]

Message to Members Re: Nantahala & Pisgah National Forest Plan

The Nantahala & Pisgah National Forest’s (the Forests) Forest Plan was finalized on February 17, 2023. RGS & AWS has been deeply engaged throughout the Forest Plan revision process advocating […]

Tennessee Grouse Hunters, Speak Up Now About the Pond Mountain Project on the Cherokee National Forest!

Act now and urge the U.S. Forest Service to increase their efforts to create needed habitat for ruffed grouse and American woodcock on the Cherokee National Forest! The Ruffed Grouse […]

Enhance Your Woodlands: Financial and Technical Resources for Woodland Owners in Tennessee and Kentucky

by Zac Chandler, Forest Wildlife Specialist Forester: Tennessee Developing a plan for your woods sounds simple, right? You consider what you would like your woods to look like and how […]

Featured Habitat Project – Southwest Virginia Update

by: Charlie Mize, RGS & AWS Public Lands Wildlife Forester – Southwest Virginia There it went, exploding out of the rhododendron and beelining for refuge in the next holler, the […]

More than 950 acres of wildlife habitat to be improved in the Daniel Boone National Forest through Stewardship Agreement with USFS

The South Red Bird Wildlife Habitat Enhancement Project is the area of focus within the Daniel Boone National Forest (KY), where RGS & AWS will be targeting the work. More than 950 acres are slated for habitat improvements through this project over the next 3 years.

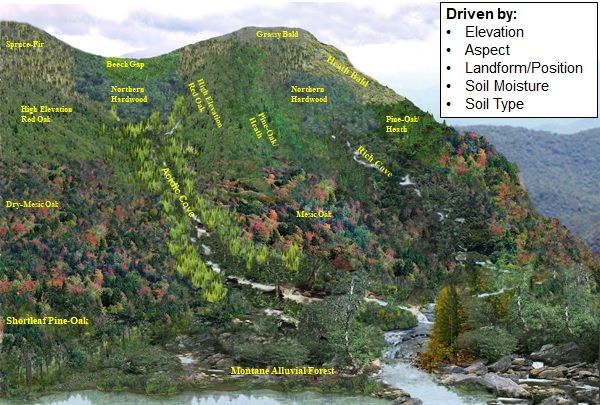

Know Your Cover: Southern Appalachian Forest Types

Southern Appalachian forests are some of the most biologically diverse forests on the planet. Western North Carolina alone contains all the major forest types you would see driving from Georgia […]

Woodcock as a Southern Bird

by Tom Keer A few winters ago, Quebec’s Don Keddy, a field trialer and grouse and woodcock hunter, had enough. The long, gray, Canadian winters are hard on bird doggers. […]

Working Lands for Wildlife — The Long View: Sustaining Our Oak Forests

Register today for this Working Lands for Wildlife virtual event. Details: Successfully managing oak forests is no easy task. It requires knowledge, forethought, and patience. In this webinar, we will take the “Long View” by looking at how human history has influenced the oak forests in the U.S. This historical grounding will allow us to look forward and consider how our actions today can ensure we restore and sustain oak forests into the future.