by Daniel Kutschied | RGS & AWS Forest Wildlife Specialist – Public Lands Georgia Ruffed grouse in North Georgia are at the southernmost extent of their range in the Eastern […]

Ecology

Featured Habitat Project – Dynamic Forest Restoration on the Cumberland Plateau in Tennessee

by Nick Biemiller | RGS & AWS Forest Conservation Director – Southern Appalachian Region The Cumberland Plateau is located at the southwestern edge of the Appalachian Mountains and includes much […]

Know Your Cover – Where to Find Woodcock

And Active Land Management for Them by Larry Partridge | RGS & AWS Lower Michigan and Eastern U.P. Forest Conservation Coordinator The American woodcock is one of our most beloved […]

NDA PODCAST: A Northern Perspective on Prescribed Fire With Ben Jones

View the original post on deerassociation.com In this episode of the Deer Season 365 podcast, we talk with Ben Jones of the Ruffed Grouse Society all about prescribed fire. Specifically, […]

Featured Habitat Project – Downeast Lakes Land Trust Woodcock Habitat Restoration Project

by Todd Waldron | RGS & AWS Forest Conservation Director – Northeast Did you know that, according to the Land Trust Alliance, there are 506 community-based and regionally active land […]

Beyond the Birds – How Habitat Benefits Us All

by Greg Hoch The conservation community does a lot of habitat work that benefits wildlife. That wildlife may be prairie grouse in grasslands, ducks in wetlands or ruffed grouse and […]

Know Your Cover: Serviceberry

By Larry Partridge | RGS & AWS Forest Conservation Coordinator – Southern and Eastern U.P. of Michigan Featured photo by: Iva Vagnerova One of my favorite springtime activities is planting […]

Funding Opportunity for Northeast Wisconsin Landowners – Joint Chiefs Project

by Stefan Nelson – RGS & AWS Forest Wildlife Specialist Private forest landowners within the Northeastern portion of Wisconsin now have an additional funding opportunity available under the Environmental Quality […]

Know Your Cover – Wild Grapes

by Charlie Mize | RGS & AWS Public Lands Wildlife Forester – SW Virginia Wild grapes (Vitis spp.) are among the sweetest snacks available to ruffed grouse, who consume them […]

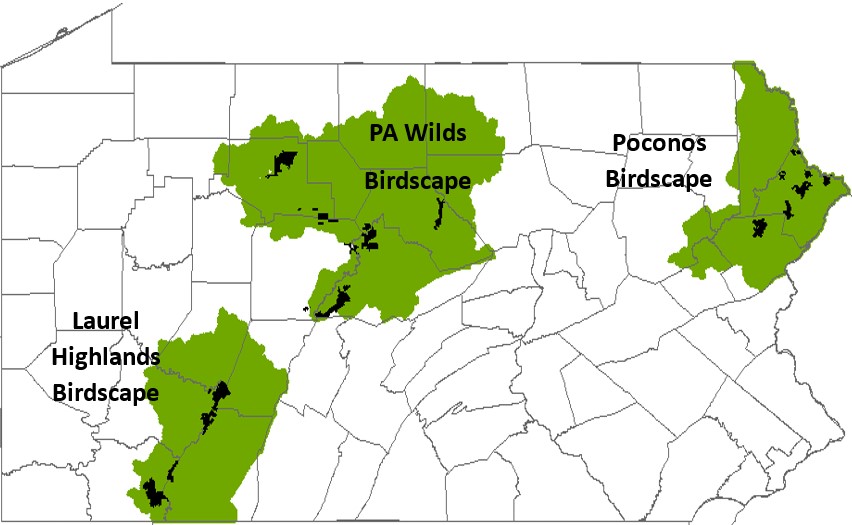

Improving Habitat on Private Lands in Pennsylvania

by Ben Larson | RGS & AWS Forest Conservation Director – Mid-Atlantic & Jake Tomlinson | RGS & AWS Forest Conservation Coordinator – Pennsylvania Those of us working on game […]