by Nick Buggia | RGS & AWS Eastern Great Lakes Regional Engagement Coordinator

Forests aren’t what comes to mind when most folks think of Indiana. However, the Hoosier State has seen its share of forestry legislation and litigation in recent years. The Huston South Project in the Hoosier National Forest is the latest skirmish regarding forest management in Indiana. For several years, the Ruffed Grouse Society & American Woodcock Society (RGS & AWS) have been pushing for science-based forest management in the Hoosier state. RGS & AWS and our conservation partners have appeared regularly in front of the Indiana legislature and the Natural Resource Commission to promote the benefits and defend the need for healthy forests in the state. Overall, we have been successful in our efforts at the state level.

Recently, however, those efforts have been focusing on The Hoosier National Forest, managed not by the state but by the U.S. Forest Service. The U.S. Forest Service has identified areas within the Hoosier where harvesting, prescribed burns and the strategic application of herbicides to combat invasive species would result in a healthier forest, creating more diversity in tree species and age class. This work would also create much-needed wildlife habitat in the state. Most wildlife species use young forest habit at some point in their life, and many depend on young forests exclusively, spending their entire lives living in them. Without this diversity, a forest not only lacks wildlife but is more susceptible to disease, fire, invasive species and drought. Therefore, managing forests for diversity is essential to ensure their overall health and sustainability so wildlife can thrive and future generations can enjoy these forests as we have.

The Huston South Vegetation Management and Restoration Project was one of the projects proposed by the U.S. Forest Service in the Hoosier National Forest. Unfortunately, this project was halted after several Indiana environmental groups sued to stop it. RGS & AWS and several other conservation organizations filed an amicus brief with the court outlining our support for the project and its overall importance to the health of the forest and wildlife. Although the ruling stopped the project from moving forward, for now, there were several positives we can take away from the judges’ comments on this case that can be applied to future projects.

For example, those who opposed this plan stated the project would jeopardize water quality, endanger wildlife, compromise forest health, increase invasive species, jeopardize outdoor recreation and exacerbate climate change. The judge found all but one of these claims were without merit. Jon Steigerwaldt, RGS & AWS Forest Conservation Director – Great Lakes/Upper Midwest, said, “The ruling on Houston South is disappointing, to say the least, yet leaves me optimistic that the issue identified can be resolved in a way that management can move forward.”

The ruling stated the U.S. Forest Service needed to gather additional information on how the project would affect the drinking water in the local community. The U.S. Forest Service has laid out in great detail the steps it would take to ensure that the local water supply remains pure and will submit additional information if they decide to continue with the project. The plaintiffs have filed to appeal the ruling in hopes a judge will support their claims that the project would endanger wildlife. The truth is, species are disappearing from Indiana and across the U.S. because these projects and others aren’t happening.

So, why is this an issue in Indiana and across the U.S? For decades, people have been bombarded with images of devastating forest fires, and we’ve been told since childhood we need to save the rainforest. What’s not communicated is how we currently manage forests in the U.S., how reducing fuel loads can reduce the intensity of forest fires and how clear cuts regenerate quickly and provide habitat for wildlife. Many well-intentioned people genuinely think they’re doing the right thing by opposing any cutting or burning when it comes to forests. For many, there’s nothing worse when thinking about a healthy forest than phrases like clear cut, burning or timber harvest. These phrases bring about images of barren landscapes and mass devastation that leave a scar on what would otherwise be a beautiful landscape. When sound management practices are used, nothing could be farther from the truth, and forests and wildlife suffer without these tools.

So, what does a healthy forest look like? A healthy forest is diverse. It has diversity in tree and plant species and age class. This diversity, in turn, provides habitat for a variety of wildlife, a place for us to recreate and can even provide economic stimulus through the harvest and sale of the renewable resources they provide. Healthy forests are more resilient against disease and invasive species; they’re essential for sustainable wildlife populations, provide a space for us to experience the outdoors and provide attractions and economic stimulus to local communities.

Perry Seitziner, President of the Indiana Chapter of the Ruffed Grouse Society and forester, summarizes it well, “Forest management is necessary for many reasons. Forest health and resiliency tops the list. Timber harvesting promotes forest diversity. Diverse forests support forest wildlife, not to mention local economies.”

Just as we manage wildlife to create a healthy and sustainable population, we must also manage forests so they can thrive. Unregulated market hunting extirpated many species across America during the 1800 and early 1900s. Today, we regulate hunting and fishing to ensure their populations remain stable and healthy. The sale of hunting and fishing licenses funds the vast majority of conservation efforts across the country. The unregulated timber harvest that helped fuel American expansion also left its mark on the landscape. In 1900 only 6% of Indiana was forested, or about 1.5 million acres. 100 years later, in 2000, 4.8million acres or more than 20% of a state known for sprawling cornfields is now covered in forest. Many wildlife species like elk, wild turkey and white-tailed deer have recovered, and forests are expanding.

Modern humans have played a part in deforestation. In the 1930s, the lack of natural grasses and trees helped exacerbate the dust bowl, and the Civilian Conservation Corps was tasked with planting many of the forests we use today. Forest disturbance isn’t something that started with the first Europeans to arrive in our country, however. First glaciers, fire, tornados, buffalo, elk, beaver and First Nation People’s agricultural practices, which included prescribed burning to clear the land, all created disturbances that allowed for the regeneration of young forests. When we started to suppress these disturbances, we began to see a lack of young forests. With modern-day forestry practices, our forests are growing, and disturbance is still a vital part of maintaining a healthy and productive forest and providing adequate habitat for wildlife.

on the Hoosier National Forest.

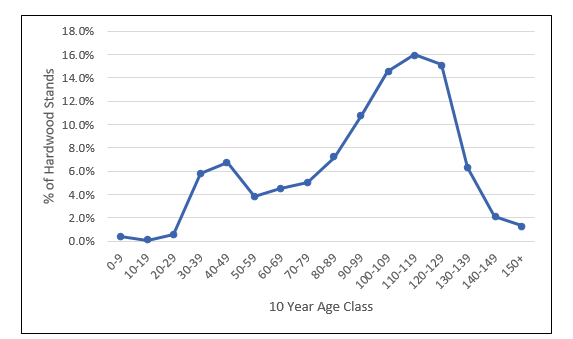

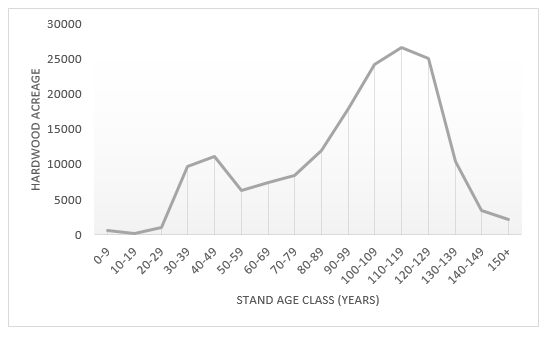

Indiana may have more forested land than it did 100 years ago, but what does that forest look like? 87% of Indiana’s forests are on state lands; in theory, this should make them easy to manage, but because of public pressure opposing harvest of any kind, it’s been a struggle for the state to maintain these forests in a way that encourages diversity and wildlife habitat. Indiana’s state forests are trending older and older, with a severe lack of forests in the 0–20-year age class. Currently, tree mortality exceeds harvest rates, meaning more trees are dying of old age than are being harvested. The resulting disparity in tree age class has led to a significant habitat loss for many Indiana Species. The ruffed grouse, and a variety of songbirds like the whip-poor-will, are actively disappearing from the landscape with no attempt at recovery. RGS & AWS worked diligently to get the ruffed grouse listed as a state endangered species. Grouse populations in Indiana have dropped over 89% since the 1980s due to the lack of young forests on the landscape. Cutting down trees doesn’t destroy a forest; it makes it more resilient. Old-growth habitat trees of 80 years in age have an important role to play as well, but when we don’t allow for disturbances like forest fires or harvesting to occur, we’re not only selfishly preventing a healthy forest form from accruing but stopping nature from doing it as well. We live in an age where multi-use management is seen in most state-owned forests – meaning these areas are managed not only for hunting but for hiking, camping, biking, horseback riding and various other activities. This is a positive thing that allows a variety of people to pursue their interests by having access to some of our nation’s greatest outdoor locations. We can’t forget we are responsible for managing not only forests but wildlife so future generations can enjoy these places and activities. Hunters and conservationists must take time to talk with our legislators, family and friends about the importance of a diverse forest and the benefits they provide to us and wildlife. If left unchanged, we’ll soon see the disappearance of many species because of a lack of unsuitable habitat.