GROUSE FACTS

Click to Hear a

Ruffed Grouse Drumming

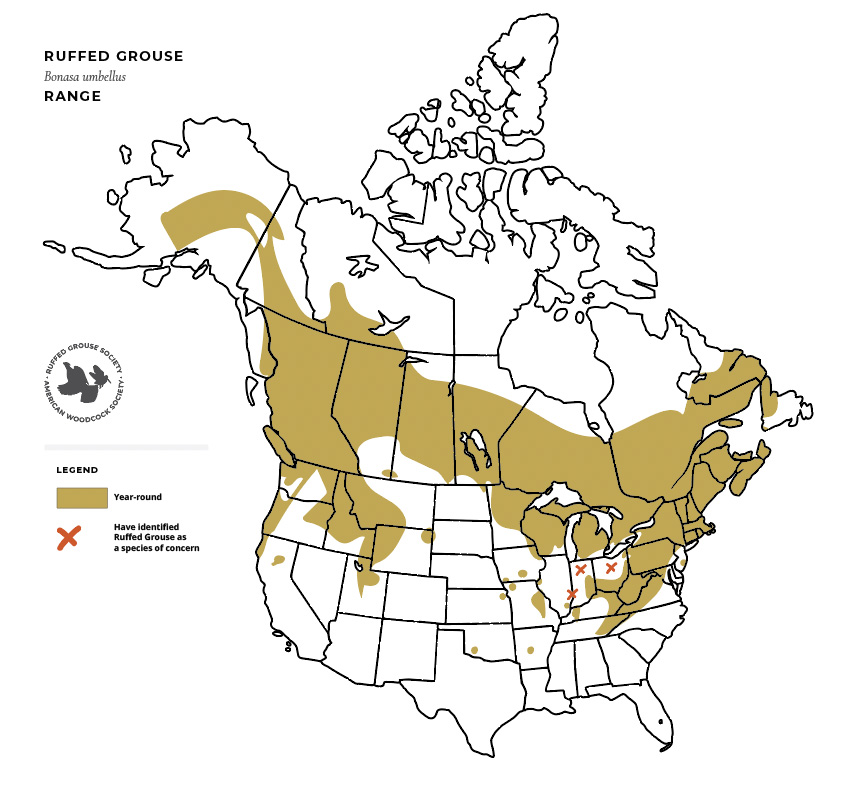

RANGE

Ruffed Grouse (Bonasa umbellus) are the most widely distributed resident game bird in North America, living now or recently in all of the Canadian Provinces and in 38 of the 49 states on the continent.

Support the critical needs

of woodland wildlife.

Their range in the East extends from near the tree-line in Labrador to northern Georgia and northeastern Alabama, and they once occurred as far south as Arkansas in the central part of the continent, although now they occur only in isolated pockets west of the Appalachians and south of the states bordering the Great Lakes.

Quite isolated populations live in the Black Hills of South Dakota and the Turtle Mountains in North Dakota. In the mountains of the West, they range south to central Wyoming and central Utah, but apparently never reached most of the mountains of Colorado, northern Arizona and northwestern New Mexico.

Ruffed Grouse have become established where they were not native in both Newfoundland and Nevada by transplanting wild-trapped birds. On the Pacific Coast, Ruffed Grouse occur on the western slopes of the Cascades and in the coastal ranges south into northwestern California (but not in the high Sierras), and north to the Yukon River valley in Alaska. By far the major portion of the Ruffed Grouse range and population is in regions where snow is an important part of the winter scene and consistently covers the ground from late November to late March, early April or later.

The Ruffed Grouse is a hearty, snow-loving, bud-eating native which thrives during severe winters that decimate flocks of partridges, quail, pheasants and turkeys.

DESCRIPTION

Ruffed Grouse are one of 10 species of grouse native to North America and are one of the smaller birds in the group, ranging from 17 to 25 oz. Ruffed Grouse are somewhat larger than pigeons, living their entire lives in wooded areas.

The males are usually slightly larger than the females, although an occasional adult female will exceed a young male in size. The name “Ruffed” was derived from the long, shiny, black or chocolate colored neck feathers that are most prominent on the male. When the cock is in full display in defense of his territory, or showing off to an interested hen, these feathers are extended into a spectacular ruff which, together with a fully fanned tail, makes him look twice his normal size.

The plumages of the two sexes are quite similar, and while about 77% of the males have unbroken dark bands near the end of their tails, many males have incomplete bands much like those of females in which the color is faded or absent on the central tail feathers. Out of a sample of nearly 1700 grouse, the same band patterns were common to both sexes among 52% of the population.

The best external basis for determining sex is a measurement of tail length. Across most of its range, a fully grown tail feather over 5-7/8 in. in length usually belongs to a male; less than 5-1/2 in. to a hen – but birds with intermediate measurements can be either male or female. When this occurs, two other procedures are useful. One is to examine the feathers on the upper side of the bird’s rump, just above the central tail feathers. If there are 2 or 3 whitish spots, the bird is probably a male; if none or one, a female. Another procedure is to compare the length of the 2nd primary flight feather from the wing tip to the length of the central tail feather. If these two feathers are about the same length, the bird is a hen; but if the tail feather is more than 3/8 in. longer than the wing feather, he’s a male!

Across most of their range Ruffed Grouse have two or more color phases. Their body feathers may be either predominately grayish or a reddish brown, and their tails vary even more in color. In the upper mid-west as many as 58 variations in tail color are recognized, lumped into 4 broad categories of silver gray, intermediate gray, brown and red.

Red-phased grouse become more prevalent in milder climates, and the gray birds are more abundant where winter climates are more severe. On the Pacific Coast from Washington south and from New York south in the Appalachians, nearly all Ruffed Grouse are red-phased. Wherever the color phases include the grays and browns, about 1/2 the hens have their own unique tail color, a “split” phase, with the two central feathers markedly redder or browner than the other 14 to 16 feathers in their tails. The subterminal band near the tip of the tail may be black or copper-colored, but is always the same color as the bird’s ruff. Males tend to have the copper or chocolate colored band about twice as often as females.

BIOLOGY AND HABITAT

Although sometimes regarded as “wilderness” birds, Ruffed Grouse have no aversion to living in close proximity to humans if the cover gives them adequate security.

In some areas of the upper Midwest, Ruffed Grouse are more abundant in woodlots scattered through populated areas than in remote wilderness forests. They thrive best where forests are kept young and vigorous by occasional clear-cut logging, or fire, and gradually diminish in numbers as forests mature and their critical food and cover resources deteriorate in the shade of a climax forest. Since the quality of grouse cover declines 15-20 years following disturbance, repeated disturbance (e.g., intensive harvests) is absolutely critical for the long-term persistence of grouse in an area.

Ruffed Grouse response to man varies greatly across their range, depending upon their experiences. In New England and the East, they are usually quite elusive and difficult to approach. But they can still be killed with a canoe paddle or thrown stones in Minnesota wilderness forests, and are not considered much of a sporting bird in western mountains and north into Canada due to their confiding “fool-hen” nature.

When the ground is bare of snow, Ruffed Grouse feed on a wide variety of green leaves and fruits, and some insects. They have also been known to eat snakes, frogs and salamanders as well. But when snow covers the ground as it does for most of the winter across the major portion of their natural range, Ruffed Grouse are almost exclusively “flower-eaters,” living on the dormant flower buds or catkins of trees such as the aspens, birches, cherries, ironwood and filberts. Extensive feeding upon flower-buds in apple orchards caused Ruffed Grouse to be placed on the list of bountied animals in some New England states at one time.

Ruffed Grouse are normally solitary in their social behavior. They do not develop a pair-bond between males and females, although there is usually at least one hen in the woods for every male. Young birds, especially, collect in temporary, loose flocks in the fall and winter, but this is not equivalent to the covey organization of the quails and partridges.

Male Ruffed Grouse are aggressively territorial throughout their adult lives, defending for their almost exclusive use a piece of woodland that is 6-10 acres in extent. Usually this is shared with one or two hens. The male grouse proclaims his property rights by engaging in a “drumming” display. This sound is made by beating his wings against the air to create a vacuum, as lightning does when it makes thunder. The drummer usually stands on a log, stone or mound of dirt when drumming, and this object is called a “drumming log.” He does not strike the log to make the noise, he only uses the “drumming log” as a stage for his display.

The drumming stage selected by a male is most likely to be about 10-12 inches above the ground, in moderately dense brush, (usually 70 to 160 stems within a 10 ft. radius) where he can maintain unrestricted surveillance over the terrain for a radius of about 60 ft. Across much of the Ruffed Grouse range there are usually mature male aspens within sight in the forest canopy overhead. Drumming occurs throughout the year, so long as his “log” is not too deeply buried under snow. In the spring, drumming becomes more frequent and prolonged as the cock grouse advertises his location to hens seeking a mate.

Courtship is brief, lasting but a few minutes, then the hen wanders away in search of a nest site, and there is no further association between the male grouse and his mate – or the brood of chicks she produces. A hen may make her nest more than 1/2 mile from the log of her mate.

Nests are hollowed-out depressions in the leaf litter, usually at the base of a tree, stump or in a clump of brush. The nest is usually in a position which allows the hen to maintain a watch for approaching predators. Sometimes hens will nest under logs or in brush piles, but this is less common, and a dangerous location.

A clutch usually contains 8 to 14 buff colored eggs when complete. Eggs are laid at a rate of about one each day and a half, so it may take 2 weeks for a clutch to be completed. Then incubation, which usually commences when the last egg is laid, takes another 24 to 26 days before the eggs hatch. A nest has to be placed so that it will not be discovered by a predator during a period of at least 5 weeks.

The chicks are precocial, which means that as soon as they have dried following hatching they are ready to leave the nest and start feeding themselves. Grouse chicks are not much larger than a man’s thumb when they leave the nest. They are surprisingly mobile and may be moving farther than 1/4 mile a day by the time they are 3 or 4 days old. They begin flying when about 5 days old, and resemble giant bumble bees in flight. The hen may lead her brood as far as 4 miles from the nest to a summer brood range during its first 10 days of life.

Although grouse broods occasionally appear on roadsides, field edges or in forest openings, these are hazardous places for young grouse to be, and broods survive best if they can remain secure in fairly uniform, moderately dense brush or sapling cover.

The growing chicks need a great deal of animal protein for muscle and feather development early in life. They feed heavily on insects and other small animals for the first few weeks, gradually shifting to a diet of green plant materials and fruits as they become larger. Chicks grow rapidly, increasing from about 1/2 ounce midgets when hatched to 17-20 oz. fully grown young birds 16 weeks later. That is a 38 to 46 fold increase in weight. At 17 weeks of age, a Ruffed Grouse is almost as large and heavy as it will ever be.

Biologists and others who want to age Ruffed Grouse rely upon certain peculiarities of the molt of the primary flight feathers. The booklet explains this aging procedure. Following the first complete molt by a 14 to 15 month old adult grouse, there are no known physical characteristics which reliably identify the age.

When about 16 to 18 weeks old, usually in September or October, the young grouse passes out of its period of adolescence and breaks away to find a home range of its own. This is the second and last time that Ruffed Grouse are highly mobile. The young males are the first to depart, when they range out seeking a vacant drumming territory, or activity center, where they can claim a drumming log. Most young males find a suitable site within 1.8 mi. of the brood range where they grew up, although some may go as far as 4.5 mi. seeking a vacant territory. Many young cocks claim a drumming log by the time they are 20 weeks old; and once they have done so, most will spend the remainder of their lives within a 200 to 300 yard radius of that log.

Young females begin leaving the brood one or two weeks later than their brothers, and they normally disperse about three times as far. Some young hens move at least 15 miles looking for the place where they’ll spend the rest of their lives.

Occasionally a hen and her brood will remain together as late as mid-January, but this is unusual, and most groups of grouse encountered in the fall and winter are composed of unrelated individuals who gather together temporarily to share a choice food resource or piece of secure cover.

During the fall dispersal period, some inexperienced young grouse crash into buildings, trees or through windows in a so-called “crazy-flight.” Sometimes they are evidently simply trying to take a short-cut when they can see through two large windows on the corner of a house. After all, young grouse in their first fall have never been confronted by something that can be seen through but not flown through, such as glass!

The future of woodland wildlife starts with generosity.

POPULATION

Ruffed Grouse normally have a short life span. From a brood of 10 or 12 hatched in late May or early June, usually 5 or 6 will have died by mid-August. Among those living to disperse during the fall shuffle, about 45% will have been lost by late fall and early winter. Another 10% die over winter and during early spring, so that only about 45% of the young grouse alive in mid-September live to their first breeding season.

In subsequent years a given cohort (a season’s crop of young birds ) continues to shrink by about 55 to 60% per year. So from 1000 chicks hatched in late spring, about 400 normally survive to early autumn, 180 survive to the following nesting season, 80 are alive a year later, 36 live to breed a 3rd time, 16 may breed a 4th time. One out of 2200 chicks hatched may live as long as 8 years.

Most Ruffed Grouse die a violent death to provide a meal for one of a number of meat-eating predators, for in the natural scheme of things, Ruffed Grouse are one of the first links in a complex food chain. Some also die from disease and parasites, or from exposure to severe weather, or accidentally by hitting trees or branches while in a panic flight after being frightened.

Across the major portion of the Ruffed Grouse range, the winged predators or raptors are most efficient at taking these birds. Although the goshawk is certainly the most efficient of all grouse predators, they are relatively uncommon and the horned owl probably kills more grouse across their range annually than any other predator. This is due to the cosmopolitan distribution of these owls and the likelihood that any woodland capable of supporting grouse will have resident horned owls, or at least be regularly visited by them. Yet, where cover is adequate, grouse can find security and maintain their abundance even when goshawks and horned owls live and nest nearby.

Conditions are seldom static in the world of the Ruffed Grouse and their numbers fluctuate from year to year, and from decade to decade. Across most of their range in the northern states, Canada and Alaska, Ruffed Grouse numbers have risen and fallen in a somewhat predictable pattern for most of this century, in what is often called a “10-year cycle”. In the Lake States, for example, periods of abundance usually coincide with years ending in 0, 1 or 2, and the bottom of the depression in years ending with 5 or 6. This is not invariable, but a general, regional trend. These “cycles” sweep across the continent more or less as a wave, beginning in the far Northwest and Northeast, and progressing southward and southeastward.

The factors responsible for these periodic fluctuations remain poorly understood, and appear to involve a number of different factors interacting with one another in different ways at different times. The one factor which does not appear to be important in annual grouse fluctuations is hunting. Generally, regulated hunting during the fall season removes grouse that are in excess of winter carrying capacity, so does not impact either grouse survival rates or population trends.

The primary causes for the short-term fluctuations in Ruffed Grouse abundance appear to be related to weather trends and variations in the quantity and quality of food resources. These are interrelated to a large degree. Superimposed upon these two basic factors is that of predation – as predators take advantage of grouse placed in jeopardy by unfavorable weather conditions or inadequate food resources. A favorable combination of weather factors and food resources may allow these grouse to survive the winter nearly immune to predation. These combinations of factors also affect annual production. If grouse spend the winter feeding on poor quality foodstuffs, or have to use an excessive amount of energy to keep warm, hens may not have sufficient reserves to produce a clutch of viable eggs, or vigorous, healthy chicks in the spring. Across most of their range, the most productive and most abundant Ruffed Grouse populations are those living where they spend most of the winter burrowed into 10 inches or more of soft, powdery snow, and emerge for only short periods once or twice a day to take a meal of the male flower buds of the aspens. Our Ruffed Grouse can be considered snow lovers or “chionophiles.” Ruffed Grouse tend to be less numerous and less productive if they live in regions where they cannot burrow in snow and feed on aspen.

There also seems to be a poorly understood relationship between the color-phase of a Ruffed Grouse and its ability to survive severe wintering conditions, and its vulnerability to predation.

Longer term changes in Ruffed Grouse abundance reflect how we have treated our woodlands and forests. These birds depend upon the food and cover resources produced by a group of short-lived trees and shrubs (e.g., aspens, cherries, hazels) growing in full sunlight which develop following a severe disturbance to the forest. In earlier times, fire and windstorm were the ecological agents periodically renewing forests and creating satisfactory habitat for Ruffed Grouse and many other species of forest wildlife. Ruffed Grouse should be considered a “fire-dependent” species in the natural scheme of things.

Our current reluctance to cut forests, even under strict management plans, and the suppression of fire to protect growing forests, have upset this natural sequence of events. In the early part of this century, farm abandonment and the recovery of forests from unregulated logging and fires produced habitats which probably resulted in the greatest abundance of grouse in recent times in most of the northern and northeastern United States. But as forests mature under protection from fire and cutting, they lose the habitat qualities Ruffed Grouse require. In many regions, Ruffed Grouse numbers have declined as forests have become more extensive and older.

Ruffed Grouse abundance can often be readily restored by proper harvest management of forested lands, or through the judicious use of prescribed fire.

The most productive management of forested lands to benefit Ruffed Grouse can be done where aspen is part of the forest community. The goal then is to provide a diversity of age classes of aspen to meet the food and cover requirements of these birds in a manner consistent with their limited mobility, by spacing small 10-40 acre aspen clearcuts through time. This will ensure that grouse can meet all of their annual needs within a fairly small area.

The same general approach can also be used in forests where aspen does not occur or is less commonbut management in these forest communities (e.g., oak forests) can be more challenging.

The future of woodland wildlife starts with generosity.

CONSERVATION

To learn more about grouse projects in your area, explore your regional page: